Reflections from Program Director, Joe Underhill, in Oslo December 10, 2017.

The 2017 Nobel Peace Prize Award Ceremony in Oslo celebrated the work of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, the twelfth group or individual to be so awarded for work on the nuclear weapons issue. Their ambitious goal is to rid the world of nuclear weapons and they were a key player in the UN’s recent passage of the Treaty to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons. The award raises the eternal question about human progress, the prospects for peace, and the very fate of humanity on the planet. In a period of time when political and cultural shifts seem particularly momentous, it is appropriate to ask if there is hope to escape from the dreadful shadow of nuclear weapons, which has loomed over us all since 1945. Social and political and economic systems seem very stable and timeless and immutable, until they aren’t. The Soviet Union was a superpower until one day it disappeared. Authoritarian governments in the Arab world seemed fixed in stone, until they collapsed in the Arab Spring. Gay marriage was socially unacceptable until suddenly it was not. These shifts in social norms are hard to predict, but Beatrice Fihn, in her mid-thirties, speaks of and for a new generation of young leaders who do not see the need, wisdom, or certainly the morality of these weapons of mass destruction.

Her Nobel Lecture, delivered along with the Hiroshima survivor Setsuko Thurlow, was a rousing call to action to rid the world of nuclear weapons, warning that we are “one tantrum away” from a potential nuclear strike. The nuclear story will end some day, she warned, with either the end of these weapons or the end of us. It is more complicated than that, since even without the weapons, our knowledge of how to make them will always be with us, and even with the most primitive weapons, humans can wreck unimaginable horrors (it just takes longer to do them). A full legal ban would not guarantee that some rogue nation did not possess a well-hidden stash of the weapons, or that a new international crisis would not prompt a chaotic scramble to re-acquire the weapons. But there is little doubt that we should move toward a world free of these weapons or at a minimum, far fewer than we currently have. Though never perfectly safe, such a world would be immeasurably safer than the one we are in now. Exactly what kind of military policies and goals we should pursue, and how to move toward them, will be part of the nuclear security dialogue sessions this coming May and June, co-sponsored by the Nobel Peace Prize Forum and the Foreign Policy Association, and funded by the Carnegie Corporation. We look forward to sharing the results and insights from those discussions at the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize Forum in Minneapolis on September 14-15th.

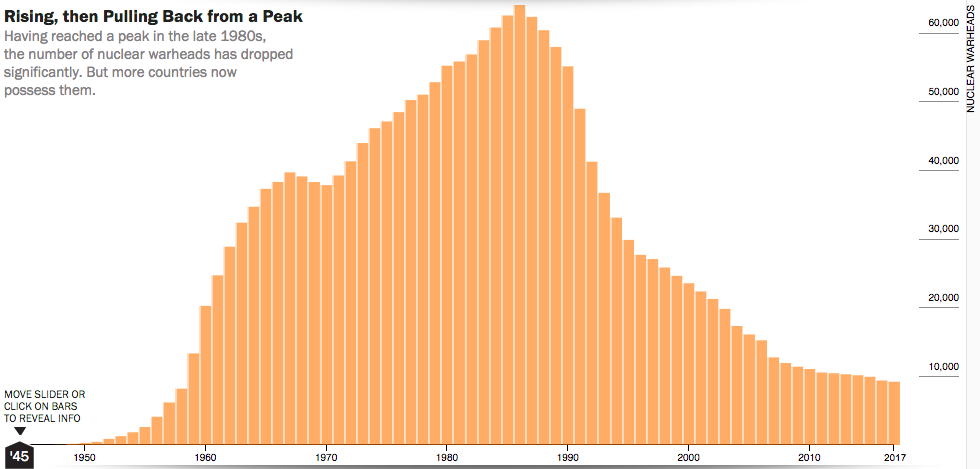

Although this goal of a nuclear-free world might seem Quixotic, we have seen dramatic progress over the last thirty years, as the graphic below demonstrates.

Over the course of the last 70 years we have seen first terrifying increases, and then dramatic decreases in the number of nuclear weapons deployed around the globe since they reached the insane peak of over 64,000 such weapons in the late 1980s. We are now at slightly less than 10,000, which is still much too high, but less than one-sixth of the previous level. This is huge progress, for which we should be glad and on which we can keep building, even if the prospects for great power diplomacy on that front appear dim in the next few years. The priority in the short term will be to keep the pressure on and prepare the foundation for the next round of U.S.-Russia arms reductions talks once there is leadership that is more open to this way of thinking in Moscow and Washington.

In the remarks delivered by the laureates, and the Chair of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, there were frequent appeals to the nuclear powers and their allies to sign the nuclear ban treaty. So far 54 countries have signed it, and only three have ratified. Interestingly, Norway itself has not signed the Nuclear Ban treaty, even though it was one of the original proponents of the “Humanitarian Pledge” and nuclear disarmament efforts that led up to the UN Nuclear Ban Treaty’s passage in the UN this July. But as part of NATO and a close ally of the U.S., Norway has chosen now to support the “nuclear umbrella” concept whereby it gains some level of the security afforded by an extension of the U.S. nuclear deterrent. The current Norwegian government has taken a more hawkish stance on the world stage, recently purchasing 52 F-35 fighter jets from the U.S., at a cost of $8.4 Billion. The increased tensions with Russia are fueling concerns about potential Russian expansion of its sphere of influence into the Baltic region. Having once been invaded and occupied by Nazi Germany, Norway remains uneasy about letting its guard down too much.

The Norwegian Foreign Minister,in opposition to the Nobel Committee’s decision, did not attend the award award ceremony, but the current Conservative Prime Minister Erna Solberg was there, and the camera panned to her repeatedly when the calls were made for countries to support the nuclear ban treaty. In its choice of Peace Prize laureates, the Nobel Committee sometimes directs its message at their own government, and in this case to all the nuclear states as well. Will they listen? Beatrice Fihn met with Prime Minister Sohlberg on December 11th, but there was no big announcement of a sudden change of heart. B ig changes do not appear imminent, but, as we have seen, it is always difficult to predict when big changes in policy and values will happen.

The presence in Oslo City Hall of some of the hibakusha, the Japanese survivors of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was powerful. For them, the change cannot come soon enough. It is almost unimaginable to think of what they went through. Humans are capable of unspeakable cruelty, short-sightedness, and violence. But we also sometimes get it right. In spaces like the General Assembly Hall of the United Nations, and in City Hall in Oslo on December 10th each year, we participate in part of building a better future, one built on kindness, patience, and hundreds of years of hard-fought wisdom. Hundreds of years from now I think people will look back and see these efforts as laying the groundwork for a more peaceful and just society and world order. The pompous posturing and petty political dynamics that seem to so preoccupy us these days will be forgotten, or viewed with a certain bemused puzzlement by future generations (who will almost certainly still have to deal with whatever future version of that political pettiness still exists). But I am confident they will admire the efforts of all those people, like the grassroots organizers of ICAN, and the wise, patient, and long-sighted diplomats working to address the challenges of climate change and nuclear threats, and be grateful for their tireless efforts to bequeath to future generations a more peaceful, just, and sustainable world.

People are tired of war and injustice, and ready to do the hard work of slowly and patiently addressing the big challenges we face. I am confident that the visions forwarded by the Nobel Peace Prize laureates are the future, not the kind of selfish, fearful, and violent behavior that is so often in the headlines. These kinds of venal behaviors, these aspects of human nature, will remain with us undoubtedly. But they will be countered by the institutions and frameworks and values being developed and strengthened in places like the UN and celebrated by the Norwegian Nobel Committee. We all look forward to being part of those efforts in the months, years, and decades ahead.